Crocodile farmer Mr Lever recently won his battle to retain a pistol for occupational use. The Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT) decision in Lever v Queensland Police Service (Weapons Licensing Branch) is significant for three reasons:

- It is another nail in the coffin in the Weapons Licensing Branch crusade to remove pistols from occupational use,

- The Tribunal was not receptive to the Weapons Licensing Branch argument that personal protection (in a person’s business and employment) is not a genuine reason to own a pistol,

- The Tribunal spent time analysing and rejecting the Weapons Licensing Branch argument that a pistol was unsuitable and a rifle must be used instead.

The crusade against occupational use of pistols

In case you missed the history, Weapons Licensing Branch has been very preoccupied refusing to renew farmers’ pistol licenses. Around two thousand people have (or had) occupational pistol licenses – mostly farmers with large farms and thick vegetation where feral pests and livestock are hard to access.

You can read the full story of Weapons Licensing Branch bully tactics and campaigning (here) and their furphy arguments about animal welfare (here).

Their crusade seems to be reaching a natural limit with two recent QCAT decisions against them (read about Salmon, the other decision, here).

Tribunal leaves open personal protection as a genuine reason for a pistol

One argument often rehashed by Weapons Licensing is that personal protection is not a genuine reason to have a pistol, even for a job where you might be attacked by animals. The Tribunal wasn’t keen on Weapons Licensing’s argument:

I consider it arguable that, if it is a genuine requirement of an applicant’s occupation that he or she have use of a weapon for personal protection, s 11(c) may be satisfied. First, each of Osborne and Bergmann were based on the weapons legislation in the respective states of New South Wales and Western Australia which expressly provided that an applicant does not have a genuine reason for possessing or using a firearm if the applicant intends to possess or use the firearm for, amongst other things, “personal protection”. No corresponding provision appears in [Queensland’s Weapons] Act. Secondly, in my view, it is at least arguable that personal protection as part of occupational health and safety is not mutually exclusive with possession of a weapon being an occupational requirement (including an occupational requirement for rural purposes). However, a decision on this issue should await a subsequent case where the issue is squarely raised for determination.

No doubt a case will eventually emerge that directly raises the issue of personal protection from animals in an occupational context. But you would’ve thought that there could be no animal more dangerous than a salty! In any case, the Tribunal appears to look favourably on the argument that personal protection from animal attacks is a legitimate OH&S issue with real relevance to occupational pistol licenses.

Sufficiency of a pistol

The Tribunal spent a lot of time dismantling the Weapons Licensing argument that a .357 pistol is unsuitable against crocodiles and that a rifle that could only be operated with two hands was a better defence. Even when one of your arms might already be in a crocodile’s mouth…

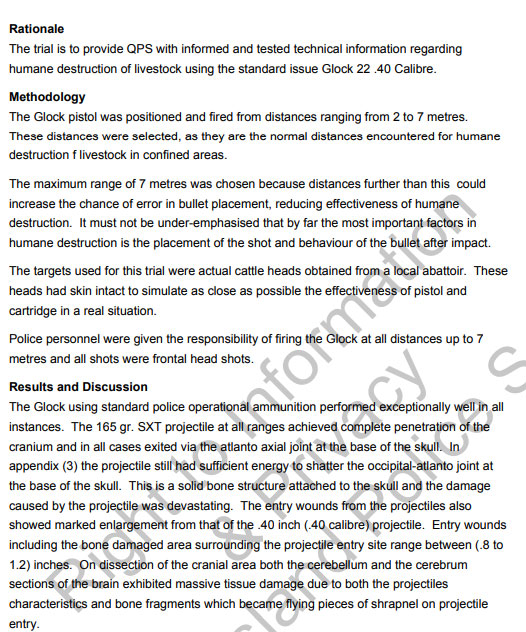

We should pause to remember that a few years ago Queensland Police engaged the Department of Agriculture’s test facility at Warwick to trial their QPS’s .40 Glock for its suitability in putting down cattle. They found it worked well (see RTI/18258):

Running this sort of ‘suitability’ argument against applicants is sailing pretty close to breaching Queensland’s model litigant rules. Those rules (are supposed to) limit how government agencies behave in litigation. They demand agencies:

- Don’t run arguments they know to be unsustainable, and

- Don’t make applicants work to prove things the agency already knows to be true.

In our experience, Weapons Licensing don’t seem anxious to observe the spirit of the model litigant rules. They seem to figure that they’re entitled to be an unlimited font of argument and they throw a lot against the wall in the hope some of it sticks.

We encourage you to read the full decision in Lever, available here:

http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/qld/QCAT//2018/225.html